Max Schubert was born in 1915 at Moculta, a Silesian Lutheran settlement in the bleached hills east of the Barossa Valley. His father, a blacksmith, worked in a small farm equipment factory where men used more hammers than screwdrivers. As no machine worked without a horse, the boy quickly became a handy horseman. At 15 years of age, he took a job as a fetch-and-carry lad at Penfolds’ winery at Nuriootpa. This put him in charge of the winery horse – there was no tractor – but his enthusiasm for delivering barrel and tank samples to the laboratory soon caught the eye of Herbert Leslie Penfold Hyland, who gave him work as a junior lab assistant.

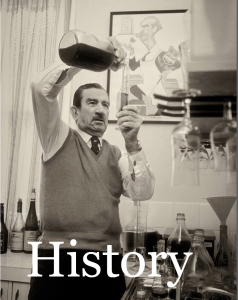

Max Schubert was born in 1915 at Moculta, a Silesian Lutheran settlement in the bleached hills east of the Barossa Valley. His father, a blacksmith, worked in a small farm equipment factory where men used more hammers than screwdrivers. As no machine worked without a horse, the boy quickly became a handy horseman. At 15 years of age, he took a job as a fetch-and-carry lad at Penfolds’ winery at Nuriootpa. This put him in charge of the winery horse – there was no tractor – but his enthusiasm for delivering barrel and tank samples to the laboratory soon caught the eye of Herbert Leslie Penfold Hyland, who gave him work as a junior lab assistant.

Grange arose from the aromas of those years. It was a world of smoke and dust. The acrid whiff of the shotgun and forge; the smithy’s leather apron; the earthiness of the manure and straw of the stables. The sweat of men and horses. The perfume of starched cotton beneath his mother’s hot iron. The fire which drove the kitchen stove. Its bubbling pots. Pickles and conserves. Plum jam. Bienenstich and streuselkuchen. Pipe tobacco. The carrots and beets Max pulled to pay for his schooling. Blood pudding and ham. And the smokehouse with its smouldering red gum sawdust and its hanging würsts and bacon, where the Schubert boys were exiled when they did wrong.

Ray Beckwith was the son of a prosperous tank maker and farm machinery dealer. Like his two brothers, he was born to science. He studied at Roseworthy College under the brilliant oenologist, Alan Robb Hickinbotham. When he took his winemaking job at Penfolds’ Nuriootpa winery in 1935, Beckwith was 23 years old. “There were 105 12-tonne fermenting tanks,” he reflected at 100 years of age. “I’d got to look after those.”

Grange arose from the entwinement of the lives of these two brilliant men.

Bacterial spoilage was rife in the cellars of those days. It was common for wineries to send a quarter of their wine to the gutter or the stills.

Beckwith was horrified that such travail produced so much waste. In 1936, on the Murray Bridge train, he had a brainwave that changed the face of winemaking forever. He realized that by controlling the pH of wine with careful addition of natural grape acid, he could defeat the destructive bacteria.

“I went down to the end of the carriage so I could sit on my suitcase, outside in the fog. I was having a smoke, listening to that clickety-clack under the dim yellow light, and I remembered I had a copy of John Fornachon’s sheet on the effect of lactobacillus on wine. I took it out and told myself, ‘I can use this!’ That was my eureka moment. I told Leslie Penfold Hyland, ‘I can crank this’ … I broached the subject of acquiring a pH meter, telling him my vision of control. I held up three brochures. ‘Which is the best?’ he asked. I told him the best was the Cambridge unit with the Morton glass electrode … ‘Get it,’ he said. I was impressed. It cost £100. My salary was £5 a week … and this was the Great Depression – there was no money!”

By the time Beckwith began work at Penfolds’ Nuriootpa winery, Schubert had been promoted to work in the laboratory at Penfolds’ Magill winery, near Adelaide. Penfold Hyland had been quick to recognize the potential of the former stable boy’s curiosity and acuity, and sent him after hours to study basic chemistry at the South Australian School of Mines.

Originally, a grange was a granary, a storehouse. With time, the term was generally applied to a country home with barns around a farmyard. In 1844, Dr Christopher Rawson Penfold and his winemaking wife, Mary, built their cottage near Makgill village, four miles from Adelaide. It looks out across the Adelaide Plain to the Gulf St Vincent, the patron of vintners and vinegar-makers. The Penfolds purchased 500 acres there on the piedmont, about half of which was already growing grain and other crops. They immediately set about planting Grenache cuttings from stock originally procured in the south of France. Within a year, the k was dropped from Makgill, but The Grange, the name they chose for their new home, was here to stay.

Between the wars, Beckwith toiled under stifling corporate secrecy at Nuriootpa, forensically solving one age-old winemaking problem after another. His pH discovery had put an immediate halt to the bacterial spoilage waste, but that was just the beginning. His many discoveries saved Penfolds millions.

Schubert, meanwhile, was soaking up vast knowledge at the Magill tasting bench. As assistant to Alfred Vesey, who prepared entries for wine shows, he soon mastered the mysterious art of blending, and kept up with Beckwith’s unfolding science of wine stabilisation. Schubert was eventually promoted to assistant winemaker. He worked closely with Beckwith on many radical ideas – together, they pioneered many aspects of the use of stainless steel and refrigeration.

From his infancy, Schubert had been painfully aware of Australia’s imprisonment of many Silesian “German” immigrants and their descendants during the First World War. Many innocents were locked up under suspicion of collaborating with the enemy. The old Deutscher names of many of their townships were Anglicised; often replaced by names of battles where the British had defeated Germany. Schubert defied the order of his managing director, Frank Penfold Hyland, who declared that any employee who went to war would be sacked. “I volunteered for service,” he would say, “to prove I was 100 per cent Australian … But I learned there was absolutely no bloody future in wars.”

Schubert never said much about the war, other than to suggest it was dusty and dirty, boring and horrid. He endured some vicious action which he never forgot. He would shyly recall saving the life of a mate when Stuka dive-bombers wiped out his convoy in north Africa, killing 200 men. He went on to serve in Greece, Crete, the Middle East, Ceylon and New Guinea, where he contracted malaria.

In one brief leave break, he married his sweetheart, Thellie Humphrys, who worked in the accounts department at Penfolds.

After the 1945 defeat of the Japanese, who were bombing northern Australia, Schubert returned to Penfolds Magill, to find himself demoted to lab assistant. Penfolds believed Beckwith was their top winemaking man, and asked him to take the role of chief winemaker at Magill. But preferring his secret career of discovery in his beloved Barossa laboratory, Beckwith insisted on promoting Schubert to the top role

Dry fino sherry boomed after the war: it was a critical contributor to Penfolds’ profits. Schubert and Beckwith worked together to perfect the rapid manufacture of finer sherry. Upon the death of Penfolds’ chairman, Frank Penfold Hyland, his widow, Gladys, took that position. She so loved the finesse of Schubert’s sherry that in 1950 she sent him to Spain to investigate the latest techniques in Jerez. This visionary move was a fortunate hiccup in the Sydney executive board’s snail-pace appreciation of the advancements being made by their radical South Australian wine scientists.

“A lot of people did a lot of good work,” Beckwith reflected half a century later. “That made a solid platform on which this big business can stand. I like to think that my generation created an infrastructure for succeeding generations to build on, and get down to the real task of winemaking … there you had the science. Now you can have the art.”

This notion was never lost on Schubert. Driven by the secret world-leading wine intelligence of Beckwith, as well as his own curiosity and constructive desire, he went north from Jerez to Bordeaux. There, Christian Cruse showed him clarets of 40 to 50 years of age. “They were still sound, and possessed magnificent bouquet and flavour,” Schubert recalled. “They were of tremendous value from an educational point of view, and imbued in me a desire to attempt to lift the rather mediocre standard of Australian red wine … With a modified approach to take account of differing conditions such as climate, soil, raw material and techniques generally, it would not be impossible to produce a wine which could stand on its own feet throughout the world and would be

capable of improvement year by year for a minimum of 20 years. In other words, something different and lasting.”

On his long, slow flight back to Australia, Schubert reflected on his even slower return from the destruction of the war a few years before. Ever the determined constructionist, he immediately began work on the recipe for his great red. He knew it would be impossible to emulate what he’d just tasted in Bordeaux. His initial compromise, a Cabernet Sauvignon blend with Malbec and Shiraz, using small French oak barrels, would be very difficult. Cabernet was in short supply, French oak was prohibitively expensive and scarce since the war, and Penfolds would want a profitable wine which could be made in large commercial volumes. Grange would have to be Shiraz fermented in Quercus alba, the white oak of Missouri. The technique would have to be revolutionary. And very, very Australian.

By the harvest of 1951, Schubert had his first Grange planned in precise detail. He would use Shiraz from the old bush vines in the Grange vineyard at Magill, and more from a favourite privately-owned vineyard of ancient bush vines at Morphett Vale in the McLaren Vale region. The fruit would be picked between 11.5 and 12 degrees Baumé, meaning the wine would end up with close to those levels of alcohol, ideally with 6.5 and 7 grams per litre total acidity.

This would be crushed into a wax-lined concrete open fermenter, sulphured, and inoculated with a cultured yeast already acclimatised to the levels of sulphur required to eliminate wild yeast infection. The cap of skins would be kept immersed in the ferment by a submerged frame of wooden heading-down boards. Maximum colour, aroma, body and flavour extraction would be achieved by regularly draining the fermenting wine from the tank until it emptied, then pumping the wine back over the skins through the slits in the heading-down board until they were once again submerged.

The ferment would take 12 days, meaning one degree Baumé of natural grape sugar would be fermented to one percentage of alcohol each day.

In practice, this was achieved by careful temperature control: as the wine was regularly drained from the fermenter, it was passed through a heat exchanger and cooled to the precise degree required to temper the yeast before being pumped back over its skins.

After the 12 days of ferment, the dry wine was divided into an experimental portion and a control. The first batch went into five raw American oak hogsheads of 300 litres each; the control into an old conventional 4550-litre oak tank. The skins left in the fermenter were pressed and stored in old 140-litre oak barrels. These pressings were used to top up the five hogsheads as they lost some wine to evaporation through their timber. Whenever the wine from either batch was racked from oak to separate its dead yeast lees, powdered tannin was added. The experimental barrels and pressings were cellared at 15 degrees Celsius.

After just one month, Schubert felt his experimental wine “was strikingly different” from the control, “with almost unlimited potential if handled correctly”. While the control “showed all the characteristics of a good, well-made wine cast in the orthodox mould”, he could even then marvel at the tremendous intensity of new oak “mixed with natural varietal fruit” that arose from his first baby Grange.

So on it went. After five vintages, Schubert was bursting with anxiety. He yearned to show the cognoscenti his wine, which he sought from the start to mature for five years before sale. But the Sydney head office showed increasing consternation at the number of mysterious bottles multiplying unsold in the drives below Magill. The vintages 1951-1956 were summoned and dispatched to Sydney for examination.

“The result was absolutely disastrous,” Schubert said. “Simply, no one liked Grange. It was unbelievable, and for the first time I had misgivings about my own assessment … Determined to prove the Sydney people wrong, numerous tastings were arranged in and around Adelaide and at Magill … the general reaction was little better than the earlier disaster in Sydney … The final blow came just before the 1957 vintage, when I received written instructions from head office to stop production.”

That dreaded letter, from the fierce managing director, Grace Longhurst, accused Schubert of “accumulating large stocks of wine which to all intents and purposes were unsaleable”. Worse, he’d recall, “The adverse criticism directed at the wine was harmful to the company image as a whole. It appeared to be the end.

But the battle-savvy Sgt. Schubert had no intention of stopping. His underground sympathisers and co-conspirators fortunately included the rakish adventurer, Jeffrey Penfold Hyland. Less Grange was made, but it was hidden from the Sydney bosses, just as the French had hidden their great vintages from marauding Germans during the war. While till his death Schubert publicly complained that he could not buy new hogsheads for three vintages, he privately joked that through a stalwart resistance collaborator in the accounts division, he smuggled some new oak through – not on a normal cooperage account, but via a machinery order, as staves.

Philip White’s text from the Book.