Born in Hobart, the same year Max Schubert created Penfolds Grange Hermitage.

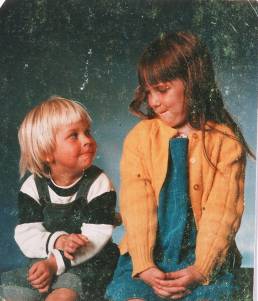

Grew up in Adelaide, married Margaret the same week Gough Whitlam came to power in 1972. Together they had two great kids Ann-Marie and Sam.

A fatal car crash in March of 1990 led to some significant life changes : See Robert Mayne’s story below.

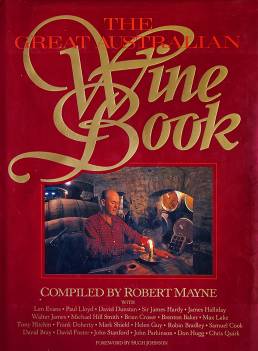

*Robert Mayne and I worked together on the Australian in Sydney in the early 1970’s. In 1983 he edited a major book on Australian Wine : ‘The Great Australian Wine ‘ book. I did the majority of the photographs for the book.

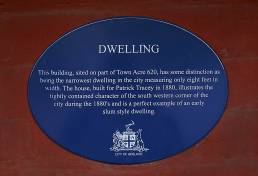

Moved into the Adelaide CBD in 1991 into a very small house, described on the City of Adelaide Heritage plaque as narrowest dwelling in the city measuring only eight feet in width, and a perfect example of an early slum style dwelling.

Now retired to Aldinga Beach, south of Adelaide in the McLaren Vale wine region, where he shares his life with Anne-Marie and their three year old Staffy Myrtle.

The day that brought life into focus

Robert Mayne : The Advertiser : May 21, 2011

PHOTOGRAPHER Milton Wordley ran a successful business, but a near-miss made him think again.

LATE one evening in 1990 photographer Milton Wordley was driving home after a photo shoot in the Adelaide Hills. He was heading towards the city in his Volvo 245 station wagon – his favourite because it comfortably held all his camera gear – when he saw a low loader coming the other way hit the concrete stanchion of the Crafers overpass.

LATE one evening in 1990 photographer Milton Wordley was driving home after a photo shoot in the Adelaide Hills. He was heading towards the city in his Volvo 245 station wagon – his favourite because it comfortably held all his camera gear – when he saw a low loader coming the other way hit the concrete stanchion of the Crafers overpass.

The truck’s load of five-tonne concrete wall sections had shifted, hit the overpass, and suddenly it all tipped into the oncoming traffic, sending an avalanche of debris tumbling towards Wordley’s Volvo. The air seemed to explode. “It was like driving into a bomb – I had photographed the IRA bombings in London in the early ’70s and this is what witnesses told me it felt like,” he recalls.

After dodging various large concrete blocks as his Volvo was progressively wrecked, Wordley ended up on the freeway verge. Once he was out of the car, his first instinct was to take a photograph. Then, as he sat down on the grass on the highway embankment and gathered his shaken wits, a woman came up and asked from where he’d seen the accident. He pointed to his car. “She said, ‘You’re lucky mate, the two people in the truck are dead’.”

“During the next couple of days I just started to think, ‘shit, you can be killed’,” Wordley says. His brush with death prompted him to review his life. He was 39 and he decided that he had to make some fundamental changes.

Things seemed OK, but in reality they were not going well, He decided to leave his wife of 20 years, with whom he had two children. He ran a photographic studio in the heart of Adelaide and employed quite a few people. That was another trouble he didn’t need.

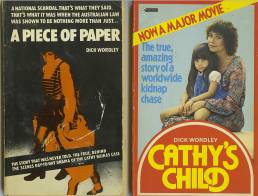

An entire lifestyle built up in the media fast lane over the previous two decades was about to change. Ever since school it had been a rush. He’d quit studies to become a printer. When his father – the late, celebrated journalist Dick Wordley – found out, he told him he if needed a job to go to the now-defunct Adelaide News. So he started as a copy boy, but being dyslexic, wasn’t cut out for journalism. Instead he moved to Messenger Press as a photographer and then worked for the new national daily, The Australian, in Sydney. Before long he was freelancing in London. He pursued a stellar career, never forgetting his father’s advice – listen. Most photographers just took pictures, his father had told him, and didn’t listen to what the story was about. He photographed queens and princes, prime ministers and captains of industry, actors, TV stars and plain everyday people. Especially everyday people. Life was exciting and great fun, he recalls, but he yearned for home and some space and a blue sky. After seeing Jack Thompson in Sunday Too Far Away, he returned to Adelaide in 1976. He took photos for The Australian, The Age, The Australian Women’s Weekly and The Bulletin. He shot Packer’s World Series Cricket.

He became interested in food and wine, appropriately for the wine state, and spent a week in Burgundy, where he fell in love with the grape variety pinot noir, which makes the great burgundies of the world. “The reason great burgundies cost so much,” he quips, “is that you’ve got to buy so many of them to find a good one.” Professionally he did well. His commercial studio near the centre of Adelaide expanded. By the late 1980s it was a hive of activity, employing up to 12 people. He specialised in mining, manufacturing and wine, and did work for the oil and gas industry. But it was costly work. The overheads for the studio were over $150,000 a year and it was losing money.

The accident provided clarity. Wordley wanted to unburden himself. So he changed everything. As well as his personal life he up-ended the business. He moved into a bed-sit in Parkside and a year later bought what he describes as the smallest house in Adelaide, where he lived – still does – with partner Anne-Marie Shin, a school principal. He was sick of the responsibility.

But not photography.

When he finally closed the studio in 2005, many thought he’d retired. This was a great exaggeration, he explains; he still owns his former studio in Selby St. “My superannuation,” he calls it. He’s also still working commercially, enjoying it more and making money from his large stock library.

Wordley says shooting pictures is very different in some ways today, but the basics remain the same. He should know – he’s seen dramatic changes in technology that have forced the film camera to give way to the digital age, opening up new challenges but also new creative opportunities. “Photography is the single most popular hobby in the world,” he says. “But while millions of pictures are taken every day, few of them are memorable. As my old man told me, it’s the mix of words and pictures that matters.”

While he started his career on film and its associated chemicals, he didn’t take long to see the benefits of digital 35mm photography. But he says he worries when the talk is about pixels not pictures. It doesn’t matter what you use, he says, as long as the photographs are good – whether they have been taken on an iPhone or a Nikon.

“Helping young photographers is taking up much of my time now, as well as involvement nationally with the Australian Institute of Professional Photographers,” he says. “Many photographers new to the business know how to take pictures, but most of them don’t know how to make a living from it.” Wordley’s son certainly does. Sam, 31, works as a paparazzo (celebrity photographer) and was based in London for 10 years before returning recently to Sydney. His daughter, Dr Ann-Marie Wordley, also considered a career in the media, earning a degree in journalism.

Today, thanks to digital technology, there are more photographs taken than ever. “It’s like it’s become a commodity and it’s often a happy snap that’s disposable, and tossed away,” Wordley says. “If there are great shots, they are getting lost in a sea of mediocrity. There’s simply too much of it to appreciate the important ones.”

Now in his 60th year, Wordley doesn’t appear to have lost any of his freshness. More than 40 years after picking up a camera, he still enjoys it. While taking great shots of people can seem daunting for the amateur photographer, he says there are a few simple rules he applies. “I like my photographs of people to feel very natural,” Wordley says.

“I still believe a photographer needs a good eye, an understanding of light and the ability to relax people to get consistently great portraits.”

ENDS : Robert Mayne : The Advertiser : May 21, 2011